(Following from yesterday's post.)

You are responsible for creating a tabletop game. What does your game do, and how does it do it?

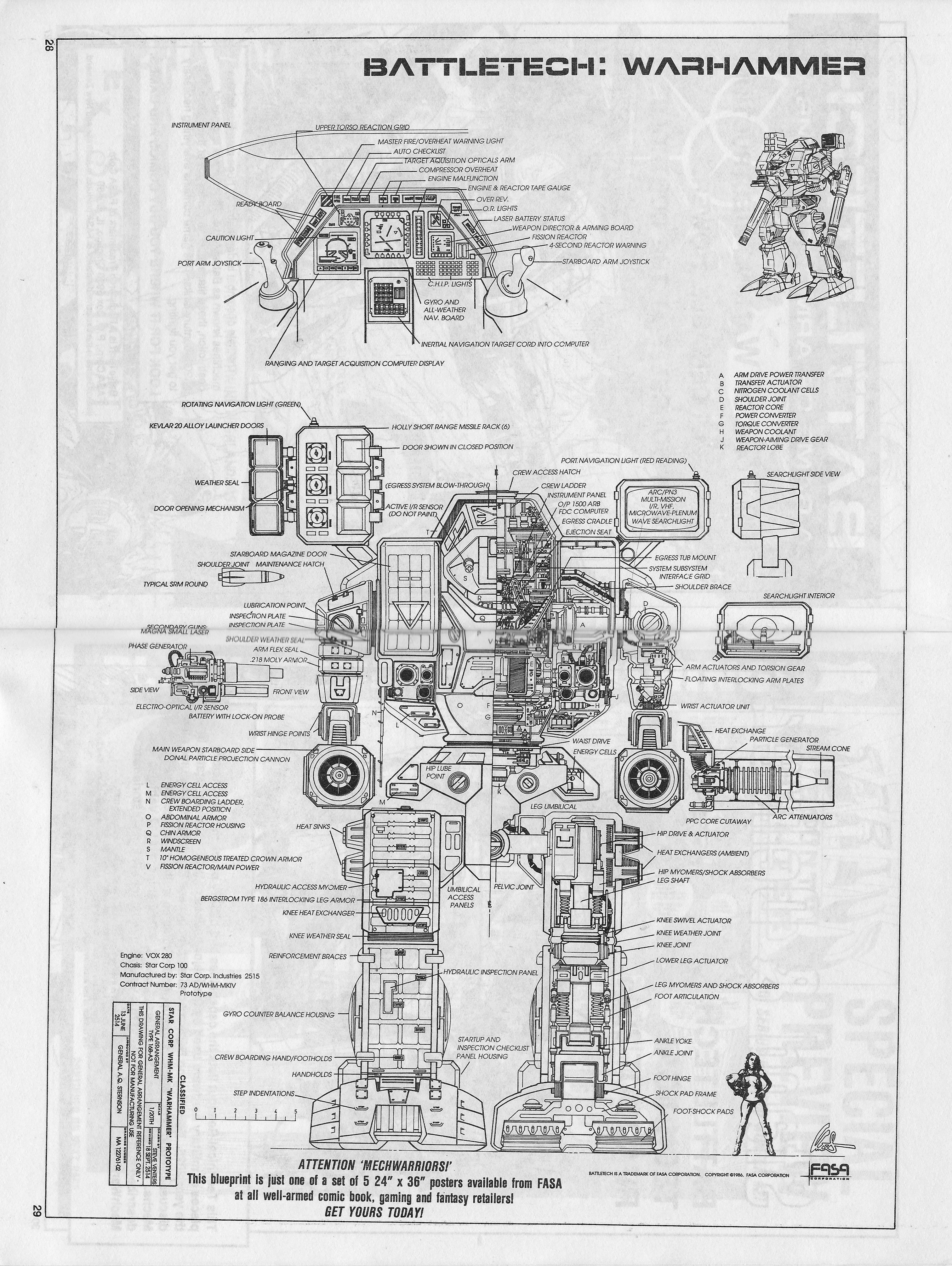

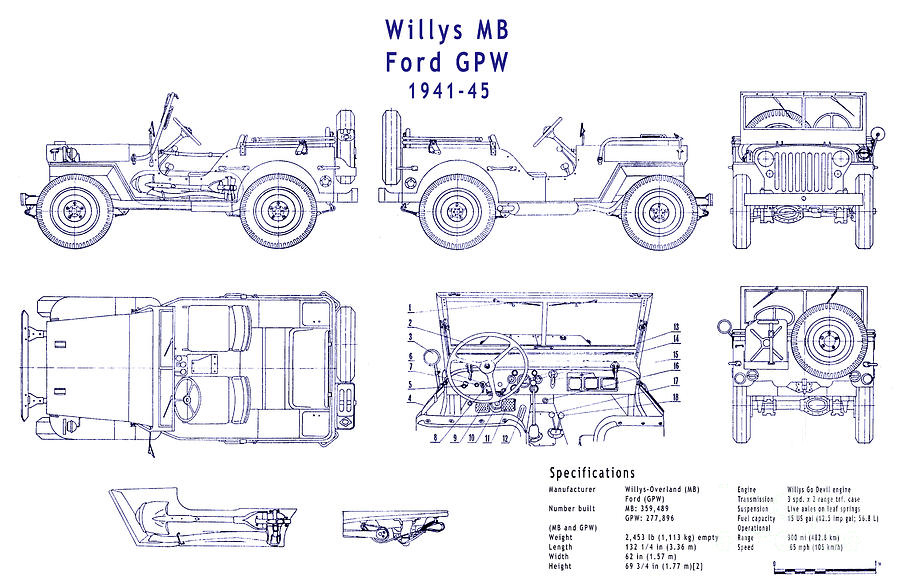

To answer your question, you must accept that what your job--"mechanical design"--means that you are building a machine to do a job. You are making this:

Or this:

Or this:

And not this:

That's a TV Writer's Storyboard

To this end, now we bring Alexander Macris' video from the other day into the picture because he hammers something that far too many of you completely fuck up.

Second Point: Unbalanced or bad game outcomes are not an inevitability in tabletop RPGs. You do not need to settle for broken rules. The bad outcomes are always a product of game design choices, and if you trace the problem back to its source you might find a way to fix it.

He will go on to talk about the importance of product testing in a slow, deliberate, well-documented, and iterative process that takes years to complete but results in a product that doesn't require ongoing Tech Support (and that's what fielding user rules questions is because you fucked up) in order to detect these problems before going to market (i.e. doing your job and justifying your paycheck) and kill them with a decisive and final fix.

There is a clear process to follow here. I don't know why no one's bothered to spell it out before, but here I am Explaining It Like You're Five.

What Does The Widget Do?

Your game design process starts at the end, as it starts with answering this question: "What is the gameplay experience that the user has by playing this game?"

Your game is a machine because it is a complex tool designed and manufactured to permit the user to achieve that experience as easily as he breathes. Everyone that uses the tool is out to achieve the same promised result; you are not selling Generic Car to Generic Moterist. You are selling Shelby Cobra GTs to a specific target audience that wants the experience of hard-driving a classic American muscle car like they're re-enacting classic chase scenes like Steve McQueen's work in Bullet.

Macris, in that video, talks about the necessity of second and third-order effects to a ruleset being made explicit to the user. While that is a failure of communication, that failure comes due to an error of design; competent design considered such effects during the design process and does not allow unintended results to come from users following the procedures put down in the manual. That's part of the job.

Exalted was notorious for this. Solar Exalts with their Pefect Attacks, Perfect Defenses, and the ability to regain Essence through Stunting sounded great until it got put down in an exhaustive analysis thread on the RPG Net forums (before the Death Cult seized control there). The result? Rocket Tag, bitch! The wholly unintended consequence was that combat was all about seeling who could run the other guy out of juice to keep Perfect Defenses going, which got even worse when the not-tested-in-the-least gameplay interactions between different Exalt types had wholly unintended outcomes that are still not fixed two editions later.

It also made an entire type of character claimed to be viable for play--"Heroic Mortals"--to be anything due to sweet fuck-all consideration for how X Procedure interacted with Y character type; as the entire mechanical base of the game was "Heroic Mortal Plus Demigod Superpowers Overlayed As A Template" that was not a minor fuckup.

(Mind you, I am sentimental towards the game and ran a campaign for three years; that doesn't mean that I didn't have to unfuck the rules because White Wolf couldn't be bothered to do their fucking jobs and instead copped out with Muh Rule Zero and other double-talking bullshit for decades.)

You avoid all of these problems by starting with a clear vision of what the game, how it works, and what the user gets out of playing it. For Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st Edition, that is evident: you play an adventurer out to make his fortune, you struggle to take big scores to pay for the training and gear needed to make the most of your potential, your deeds actualize that potential into real power in the setting, and if you succeed you realize that potential and become a heroic figure that everyone fears or loves (or both)- but this requires mastering habits of resilience and persistence, failing and trying again until at last a character you play conquers all before him and rises to power. It's a wargame; the best warlord wins.

How Does Your Widget Do It?

Your rules manual needs to Keep It Simple. This means that every procedure needs to be short, concise, and direct. Cut your gameplay procedure design down to the minimum that is required to achieve the desired result. Check your rules design for second and third-order effects generated by the interactions between your procedures--see Macris' video again for examples--and test your design until it can't go wrong.

Not until it works. Not until you get it right. You test it until your target audience, coming at it cold and stupid, cannot possibly get it wrong. (If you don't know who that is by now, you fucked up.)

Remember Feng Shui? The RPG version of Shadowfist? At first glance, seems okay. You pick a template, adjust a few numbers as allowed, pick some gear and GO! But soon it fell flat; the game felt like playing Super Robot Wars for people with Down's Syndrome- you talked (Visual Novel segment), then you fought (where the rules are and thus the game is), repeat until you're bored or it's over and you get Pity XP for not walking out or falling asleep so you can get another nonsense scenario next week. The World of Synnibarr is a better designed game that this- Nazi Gestapo Elves and all.

That was a game that had the lofty ambition of making the game feel like you're playing out a Hong Kong action movie, which were gaining a Western audience in the 1990s due to Jackie Chan and Chow Yun Fat and John Woo making inroads in Hollywood at that time. It was also "the Shadowfist RPG".

These are not wholly overlapping audiences.

What resulted was something unsatisfying to both the serious HK movie fans and the card game fans. Despite a second edition, it limped along as an also-ran game in an also-ran company's catalog. There was no serious consideration for campaign play despite it being a predictable demand, and the trope-emulation elements were too weak to maintain a long-term appeal to the film buff set. Along with the usual copout--"Rule Zero!"--it is no surprise that the game is nigh-forgotten now.

You don't sell a Writer's Room exercise kit to a wargame audience, which is what the game comes down to (and Hong Kong Action Theater was more explicit in doing). You don't half-ass your gameplay procedures by saying "tropes, LOL!"

You don't let major rules errors see the light of day, especially if you're doing traditional print runs and not Print On Demand (which is trivial to fix). (Siembieda, buddy, looking at you.) You go to that audience, you see what they're playing (Revealed Preference) and what they're complaining about the status quo and then you sell the fix to them. If some smooth-talking Texan going on about a fictional war machine for two hours can grasp this, you have no excuse for not doing so.

What Your User Gets Out Of It?

Even if your design is solid, you can still screw the pooch by not given the target audience what they're expecting.

This is not just communication. This is you, by doing product testing, making sure that your design process results in creating the machine which delivers the gameplay experience that you promised to them.

That's what kills so many hopefuls. Do we need Yet Another Fantasy Adventure Wargame--another proper RPG--out there? No, we don't. We need most of those out there to An Hero and make room for something that actually has market appeal.

And no, you don't know that your baby has that. Not even you, Magic-Users By The Water. That's why you pay people to do market research; I hope that they're smart enough to just sit down, watch the scene, see what's being complained about and report that back. If the Military Industrial Complex can make bank keeping new and improved war material coming out of the factories, you people should have no problem figuring out how to make a proper RPG in a field far from where The Game That Matters dominates.

You should. Too many did not.

This leads to the first error: hubris. Successful products satisfying an existing demand because that demand stems from an unsolved problem. Too many games are solutions looking for problems THAT DO NOT EXIST. As these games are utterly dependent upon the Network Effect for their value, the marketplace space for a given type of game is much smaller than commonly believed.

Swallow that pride and serve your audience instead if you want to make bank making and selling games. You sell the fixes to their problems and you make bank. You schlep them something they never asked for and you're going to go broke.

AD&D1e's users get the solid fantastic adventure experience, built on a framework of Braunstein and Strategos while retaining gameplay structure and feedback loops going al the way back to Kriegspiel, and as it draws from far more than Generic Fantasy (READ APPENDIX N!) that's a far-ranging territory already covered.

Pendragon still nails Knightly Adventure And Romance better than anything else, and that extends to its alternative forms (Paladin, Prince Valiant, etc.), as it is a distinct experience from AD&D while drawing from the same ludological and literary roots.

Classic Traveller retains its power despite being decades away from the spotlight, such that every other space adventure game is compared to it- including its successors. It has a separate and distinct play experience from both of the aforementioned, and has itself influenced many others after it (e.g. Twilight 2000).

Does your game have a unique experience with mass appeal? Does digitizing it make it worse? Does your design break (i.e. does not deliver intended results) if used as-written? If you don't answer "Yes" to the first two and "No" to the last, then you fucked up- go back and fix it until you can.

Tomorrow we move on to talk Writing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Anonymous comments are banned. Pick a name, and "Unknown" (et. al.) doesn't count.